Understanding independent clauses is important for structuring sentences correctly. But what is an independent clause?

No, it’s not Santa Claus’s rebellious child. Independent clauses are the main part of a sentence. Let’s dive into exactly what an independent clause is, how to spot one, and how to write one.

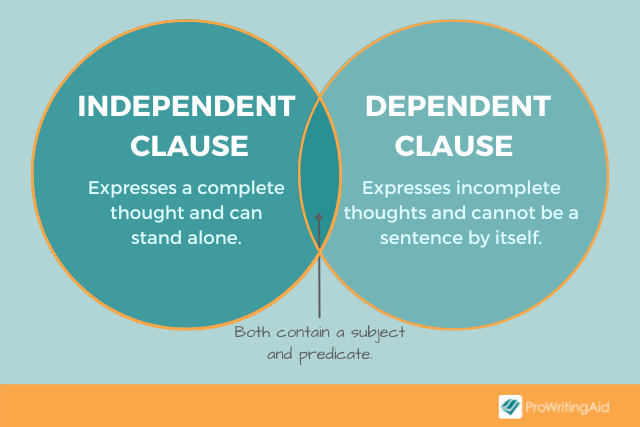

An independent clause is also called the main clause. It expresses a complete thought, and it can stand alone as a sentence. Its counterpart is a dependent clause, which cannot stand alone. Dependent and independent clauses can combine to make different types of sentences.

With all this talk of independent and dependent clauses, you might be wondering what exactly a clause is. A clause is a phrase that contains a subject and a verb or verb phrase.

These subject and verbs must be related. Typically, this means that the subject is doing the verb in that clause, although the verb might not be an action verb (for example, is isn't an action verb). The verb might also be negated (e.g. "not" → not going).

A clause is a type of phrase, or group of words, but phrases do not have to be clauses. If there is a subject, stated or implied, related to a verb, then the phrase is a clause.

What does this look like?

The first phrase is not a clause. There is no subject or verb. The second phrase is also not a clause because there is a verb but no subject.

In the third and fourth phrases, the subject is "he" and the verb is "went." The third phrase is an independent clause. We could capitalize the first word and put a period on the end, and it would be a complete sentence. The fourth phrase is a dependent clause because it does not express a complete thought.

We’ll look at the differences between dependent and independent clauses in the next section. Here's a quick video to help you review what you've learned so far:

When we say that an independent clause can stand on its own as a sentence, we mean that it expresses one entire thought. Dependent clauses represent incomplete thoughts.

Imagine you’re talking to your grandmother. She’s telling you a story about something from her childhood, but she keeps trailing off. She says, "When I met Elvis Presley," and then she just stops. Grandma! You can’t just start a story like that and not finish it! What happened when you met Elvis?

That’s a dependent clause. It’s an incomplete thought. If Grandma said, "I met Elvis Presley," that is a complete thought, although hopefully she continues the story! That’s an independent clause. She could leave the story there, and you will know this new fact about her. You might want to know more, but her statement isn’t missing anything.

Independent clauses express one complete thought. There is only one type of independent clause. However, there are three main types of dependent clauses.

A dependent clause can function in several different ways. It can function as a noun, an adjective, or an adverb. These are called nominal, adjectival, and adverbial dependent clauses, respectively.

Independent clauses can be sentences, or they can be one part of a sentence. It depends on the type of sentence, which we’ll cover in the next section.

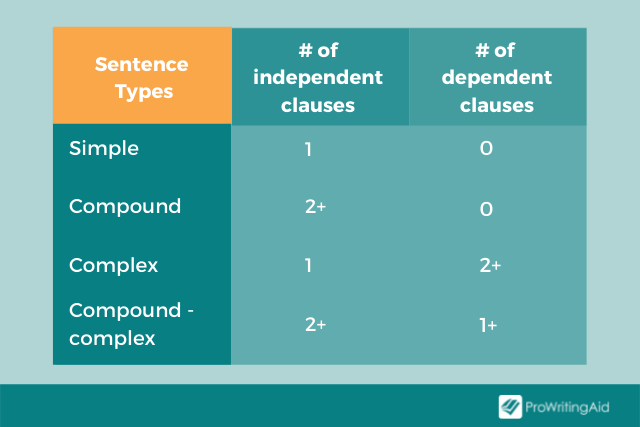

Every complete sentence has an independent clause, but not every sentence contains a dependent clause. The number of independent and dependent clauses in a sentence tells you what type of sentence it is.

To determine whether a clause is dependent or independent, you must ask yourself if it can stand alone as a sentence. Does it sound complete when you read it out loud?

Let’s look at some example sentences. Can you identify the dependent and independent clauses in each?

The first example expresses only one complete thought. It’s a simple sentence. The second example has a dependent clause (before Santa arrived) and an independent clause (we had a big holiday party).

The third example contains two independent clauses. "The adults drank hot cocoa" and "the kids played in the snow" are both complete thoughts. This makes it a compound sentence

Finally, the last sentence contains one dependent clause (after the party was over) and two independent clauses (we all went home/the children went to bed). It’s a compound-complex sentence.

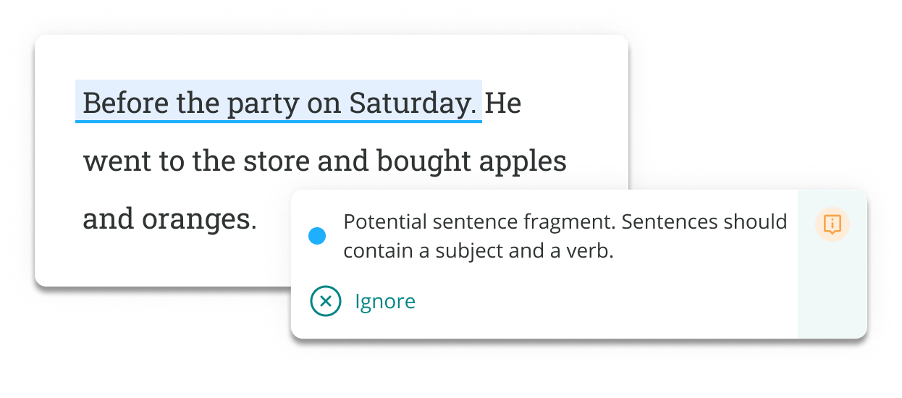

Using a dependent clause as a sentence creates a sentence fragment—an incomplete sentence that isn't grammatically correct. If you're writing an academic essay, a report, or any formal communication, you should avoid using sentence fragments.

Sentence fragments appear in fiction writing for effect, but if you use them too often it will become distracting. ProWritingAid's Realtime Report will highlight any sentence fragments in your writing and remind you to add a subject or verb. And if you want to use the fragment? Just hit ignore.

Now that you know what an independent clause is and how to identify it, we can go one step further into understanding this important grammar feature. What are the components that make up an independent clause?

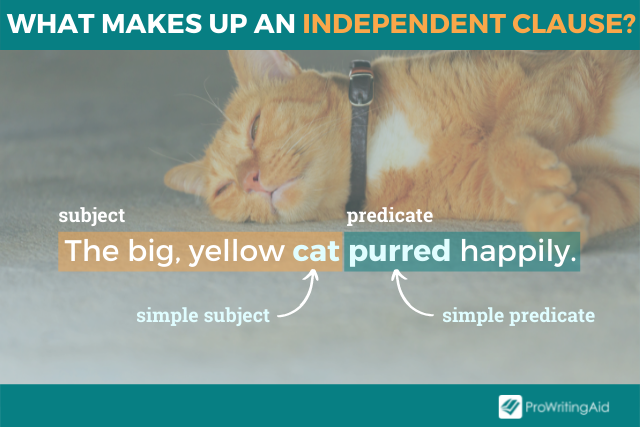

An independent clause is comprised of a subject and a predicate. The subject is the "who" or "what" of a clause. It is the noun or noun phrase that is doing the verb. A simple subject contains just the noun or pronoun with no additional modifiers.

A predicate is the part of a clause that contains the verb or verb phrase. It’s the action or state of being of a clause. The predicate doesn't have to contain an action—it can also include "be verbs" (like is, was, was not, etc). A simple predicate is just the verb or verb phrase and none of the additional modifying words.

We wrote a whole article on subjects and predicates to help you understand what they are and how to use them.

Here’s what this looks like in an independent clause:

We know that the example is an independent clause because it contains a subject and a predicate and expresses a complete thought.

Since we don’t write exclusively in simple sentences, it’s important to know how to connect independent clauses to other clauses. We connect independent clauses differently, depending on what type of clause it’s connected to.

We can connect two independent clauses in a few different ways. The first method is to use a coordinating conjunction.

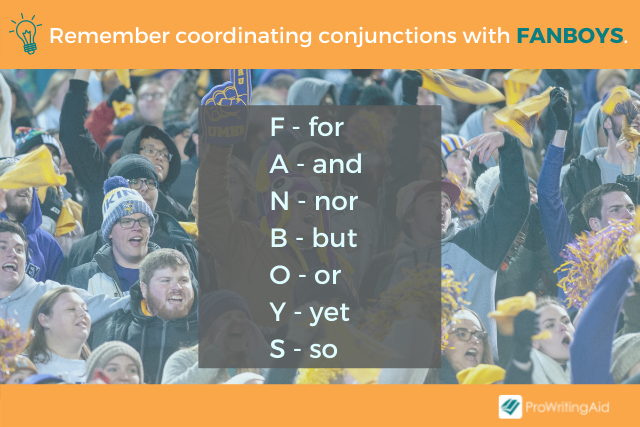

There are seven coordinating conjunctions in English: for, and, nor, but, or, yet, so. You can remember these with the acronym FANBOYS.

Note that "so" can be either a coordinating conjunction or a subordinating conjunction. We’ll cover those in the next section.

When you combine two independent clauses with a coordinating conjunction, you must place a comma before the conjunction. Here’s an example:

We place the comma directly after the first independent clause and before the coordinating conjunction. There is no comma after the conjunction.

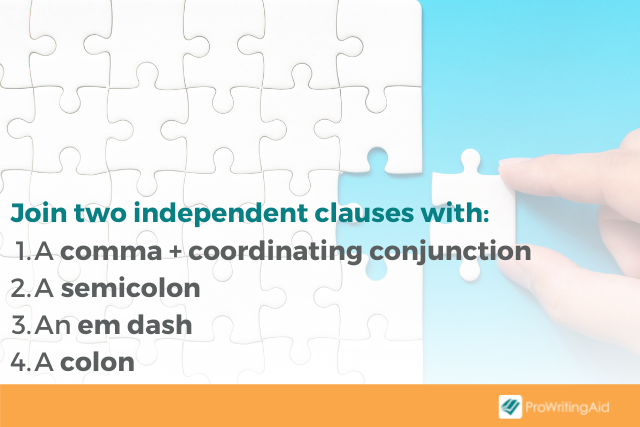

You don’t have to use a coordinating conjunction to connect independent clauses. You can also use certain punctuation marks. These are semicolons, em dashes, and colons.

When you use a semicolon, you do not include a coordinating conjunction. You can use a transitional word or phrase after the semicolon, like "however" or "as a result." These are called independent markers.

Image showing how to join independent clauses" />

Image showing how to join independent clauses" />

Here is what using a semicolon to join independent clauses looks like:

Em dashes and colons are not directly interchangeable with semicolons. Em dashes are used to mark a dramatic break in the sentence and add emphasis. They can also denote a change in tone.

You don’t usually see colons separating independent clauses. The independent clauses must be closely related to use a colon. The emphasis should also be on the second clause.

Notice that no matter whether we use a semicolon, colon, or em dash to connect two independent clauses, we do not use a coordinating conjunction.

A comma splice is when you connect two independent clauses with only a comma. It is grammatically incorrect. To fix a comma splice, you can:

Here’s what this looks like:

If you still get confused on how to connect independent clauses, ProWritingAid can help. The editing tool will point out punctuation errors like comma splices so you can feel confident about your grammar.

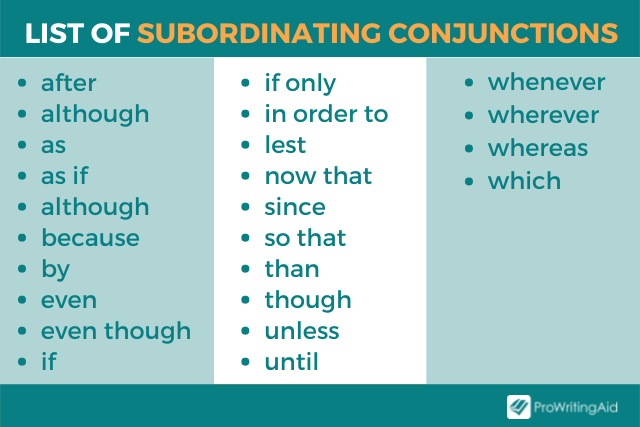

A dependent clause is also called a subordinate clause. We use subordinating conjunctions to connect dependent clauses to independent clauses.

Subordinating conjunctions include words like:

When a dependent clause precedes an independent clause, place a comma after the dependent clause, like in the example below.

When dependent clauses follow independent clauses, we usually do not use a comma before the subordinating conjunction. Here’s the same example flipped around:

However, you can place a comma before a subordinating conjunction when the conjunction is an adverb of concession.

An adverbial dependent clause that concedes a point made in the independent clause uses an adverb of concession such as although, even though, though, even if, whereas, while.

If you aren’t sure if the conjunction is an adverb of concession, ask yourself if the dependent clause contradicts the main idea in some way.

Here are a few examples of adverbs of concession that follow independent clauses.

In general, however, you can remember that a comma comes after a dependent clause but not before one.

Let’s make sure we really understand independent clauses with a few more examples. We’ve underlined the independent clauses.

We hope you feel confident about identifying and using independent clauses after this article. Do you struggle with constructing sentences and punctuating clauses? Let us know in the comments.

Check every email, essay, or story for grammar mistakes. Fix them before you press send.