Vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) is when urine flows back from the bladder to the kidneys. It can lead to infections. Treatment may include antibiotics or surgery.

About 1-3% of all infants and children have a condition called vesicoureteral reflux (VUR), which means some of their urine flows in the wrong direction after entering the bladder. Some of the urine flows back up toward the kidneys and can increase the chance of developing a urinary tract infection (UTI).

UTIs that reach the kidneys can cause health problems. That's why it's important to diagnose and monitor VUR early and treat it if needed.

Most children who have VUR are born with it, and doctors aren't sure of the cause. It appears to happen by chance. Researchers are studying inherited or genetic factors (conditions the children are born with) that may be the cause.

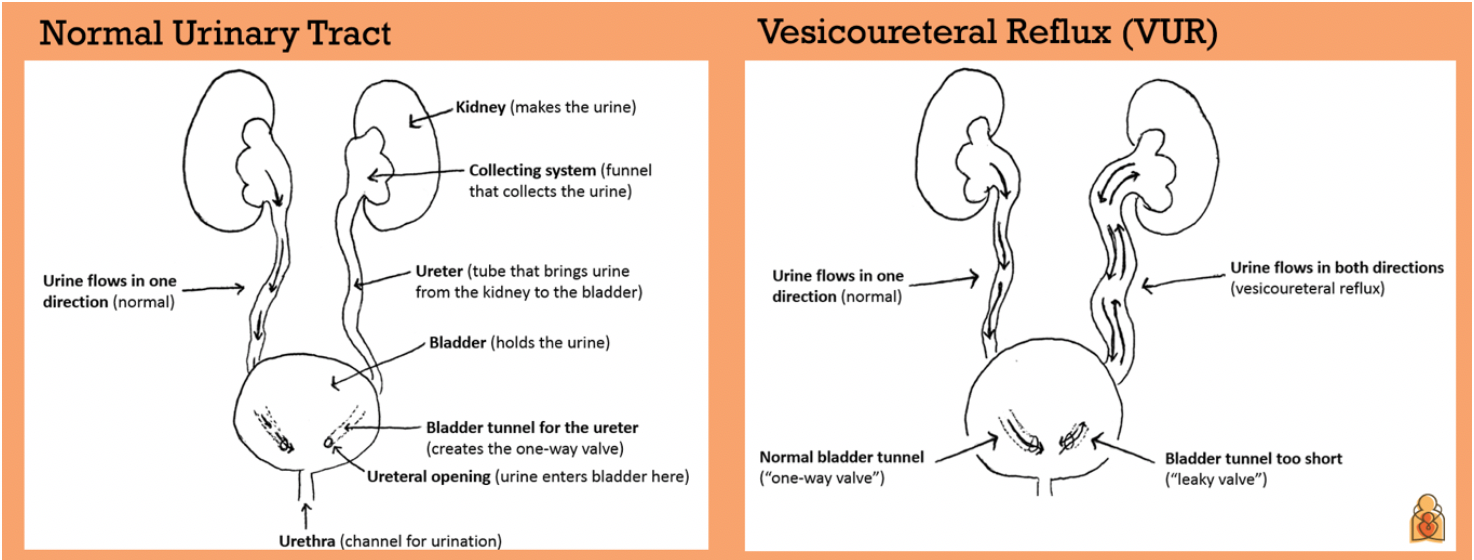

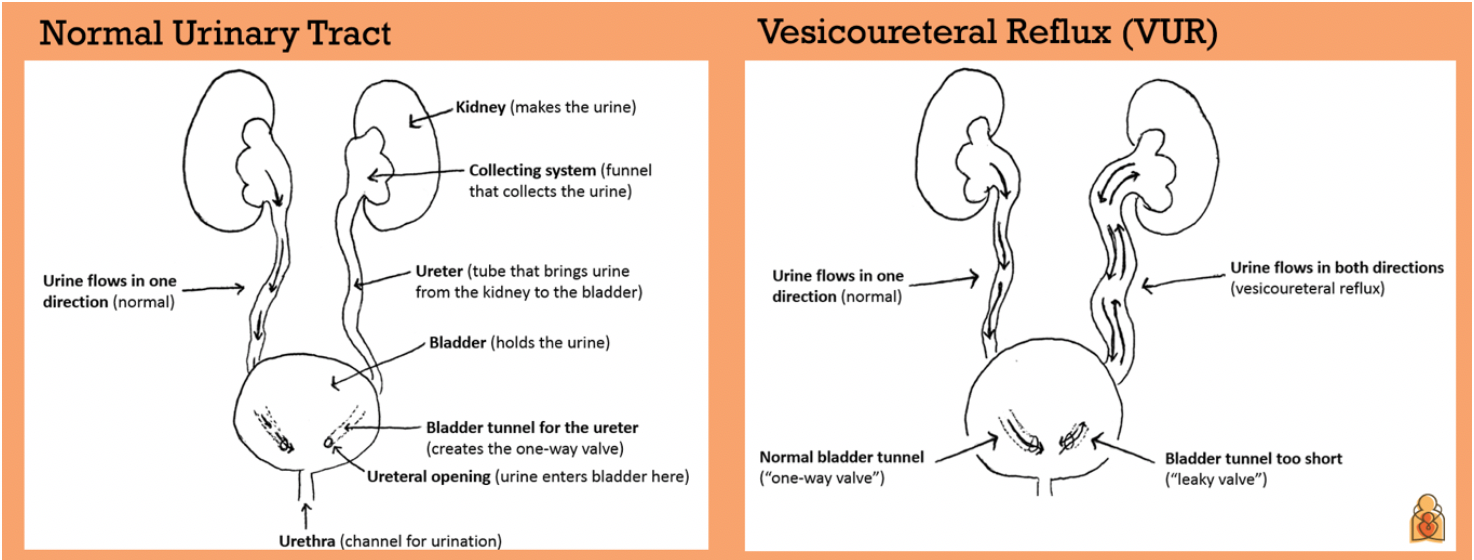

A child's urinary tract is usually a one-way street (see pictures below). The urine flows down from each kidney through tubes called ureters. The ureters enter the bladder through a tunnel of bladder muscle that creates special one-way valves to prevent urine from going back up into the kidneys. The urine in the bladder travels out of the body through another tube called the urethra.

In VUR, the tunnel in the bladder for one or both ureters may be too short, making the valve "leaky." VUR can also happen as a result of the bladder not emptying normally. This is a less common cause of VUR.

VUR doesn't usually cause symptoms until a child develops a UTI.

UTIs can be in the bladder or the kidney.

VUR may also be suspected if a child has hydronephrosis, kidney swelling caused by the build-up of fluid. This can be seen on a kidney ultrasound.

VUR is diagnosed by a test called a voiding cysto-urethrogram (VCUG). A VCUG is usually done if:

A thin plastic tube called a catheter is placed into the urethra, and the bladder is filled with a special fluid that can be seen by x-ray. The test is not painful, but the child may have some stress and short-term discomfort from placing the catheter.

X-rays are taken as the bladder fills up. VUR is diagnosed if the liquid goes the wrong way up a ureter and back into a kidney.

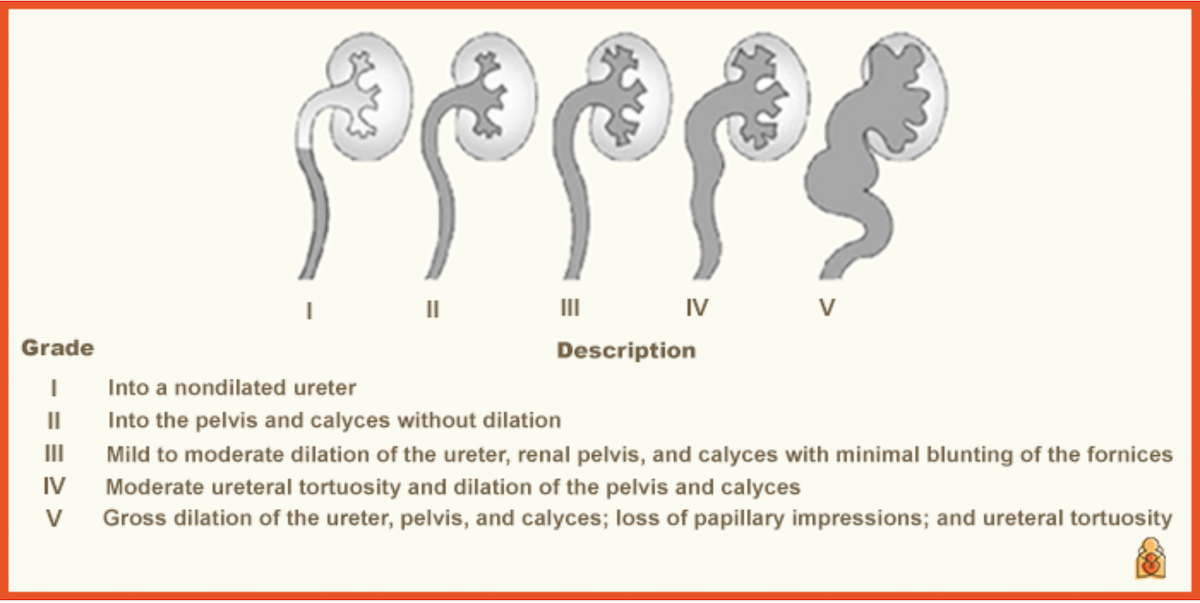

VUR is graded between 1 (mild) to 5 (worst). The grade is based on how far the urine backs up and how wide the ureter is. Children who have lower grades of VUR (1-2) found early in childhood have a good chance of outgrowing it within 1 to 5 years.

Pediatric specialists who care for children with VUR include:

Treatment for VUR is based on a child's age, the grade of their VUR, and whether it's causing any problems, such as a lot of UTIs. In many cases, VUR will get better on its own with age.

These procedures are common, generally very safe, and have excellent long-term success.

Continue to help your child with healthy bladder and bowel habits. All potty-trained children with VUR need to work on this to help prevent UTIs.

Avoid constipation. Most children get constipated. This is common around the age of potty training when they are learning to hold their bowels. Constipation makes it harder to empty the bladder and increases the risk of a UTI. It is important to avoid or treat constipation.

Discourage "holding it." Drinking enough water and eating a high-fiber diet may prevent or treat constipation. Some children may need a gentle daily laxative. Children should have a soft bowel movement every day.

It is also important that children completely empty their bladder every 2-3 hours when they are awake. Children should avoid holding their urine for long periods. This helps keep the bladder clean and prevents UTIs.

If your child has any of these symptoms, call your pediatrician. Based on test results, your pediatrician will decide whether your child needs to start treatment with an antibiotic either at home or in the hospital.

Many children grow out of VUR over time, often by age 5. Finding VUR early and monitoring it closely with your child's doctors--and getting treatment if needed--will help avoid any lasting problems.

American Academy of Pediatrics, American Society of Pediatric Nephrology and the National Kidney Foundation Patient Education Collaborative (Copyright 2019)

The information contained on this Web site should not be used as a substitute for the medical care and advice of your pediatrician. There may be variations in treatment that your pediatrician may recommend based on individual facts and circumstances.

© 2024 National Kidney Foundation, Inc. This material does not constitute medical advice. It is intended for informational purposes only. Please consult a physician for specific treatment recommendations.